In the Vernacular

By Carol Lee Flinders

I’ve been besotted with European women mystics like Julian of Norwich and Mechthild of Magdeburg for more decades now than I enjoy counting. If I had to identify one way in which my understanding of these figures has deepened over time, I’d probably start with the term “vernacular mysticism.”

I’ve been besotted with European women mystics like Julian of Norwich and Mechthild of Magdeburg for more decades now than I enjoy counting. If I had to identify one way in which my understanding of these figures has deepened over time, I’d probably start with the term “vernacular mysticism.”

Religious historians invoke the phrase to underscore the very real differences between medieval mystics who spoke and wrote in Latin — university men, and especially the “Church Fathers” — and those who came into prominence around the time of Saint Francis and afterwards, who were often itinerant, and poor on purpose — members and founders, of non-traditional orders. Women as well as men, these individuals typically spoke and wrote in the languages that were only then taking shape across Europe: French, Italian, German, English, Spanish...

Julian of Norwich, for example, wrote in the same Middle English that Chaucer did. Her prose is every bit as fresh, lively, rhythmic, and unexpected as his — hot to the touch. Her metaphors are not lifted from classical sources, they are freshly minted and drawn directly from the visible, palpable world around her — the raindrops flowing down her window, the hazel nut in the palm of her hand. And even as the mind’s eye assents when we read the Showings ( “Yes, I’ve seen that ”), so, I think, does the mind itself, and the heart. Another door begins to open to Julian’s astonishing insistence, for example, that “Jesus is our mother.”

Far-reaching changes were taking place all across Europe. Prior to the middle of the eleventh century, throughout the so-called “Dark Ages,” monasteries had been the focal points of Christianity. But even as the highways and marketplaces of Europe were coming to life, the Church awoke to a new vision of itself and its responsibilities to “the children of God.” With the Gregorian Reforms, the Church transformed itself into an elaborately hierarchical organization centralized in Rome. It was the most advanced bureaucracy in Europe and a phenomenally efficient delivery system for the Word of God (efficient except, of course, that to his vastly enlarged multi-lingual congregation, God would continue to speak in Latin). It was staffed by priests — university-educated men whose religious authority derived not from personal sanctity but from scholarship and ecclesiastical appointment. The whole edifice would of course be off limits to women.

And yet, of course, that was always only ever the edifice. Beneath the busy bureaucratic structures, and in spite of them, authentic religious life kept going. Mystics went on being mystics. Their visions were set down and the manuscripts hidden away — not, thank goodness, forever. After five or six hundred years, just when women needed them most, Julian and Mechthild, Hildegard and the whole glorious troop would show up. . .

Sometime in the early "aughts," a term came into circulation that has seemed to me fully applicable to these women and their role vis a vis not just the church but patriarchy itself. It is “outsider-insider,” and it was coined by jurist Anita Hill.

At the end of 2002, Time magazine had named as ”Persons of the Year” three women who had “blown the whistle” at their places of work: two of them at big corporations, and one at the FBI. No mean whistleblower herself, Hill wrote a thoughtful piece about what they had accomplished and why it mattered. Each of the three women had risen up through the ranks to positions of apparent power and authority. To all appearances, they were now “insiders.” But of course the uppermost echelons of corporate and government institutions functioned as “warrior cultures.” Women had no real voice at that level.

The good news, of course, was that since they had nothing invested in the “bro” world, they also had nothing to gain from keeping quiet about the malfeasances they saw. They could see and speak the truth as male executives could not and would not. They were “outsider-insiders.”

And so, I believe, were Julian, Mechthild, Clare, and their sisters-in-spirit. They had had firsthand experience of ultimate reality — had seen it and tasted it and knew it, and they would not be silenced. Think Catherine of Siena fearlessly dressing down the Pope (two popes, actually, but that’s a story for another day).

“Vernacular” doesn’t just mean “not-Latin.” To write or speak in the vernacular is to embrace what is local and to focus on what is right in front of you... it means choosing the concrete over the abstract, the informal and improvisational over the formal and formulaic.

“Street” over academic...

None of the women in question were more street than the Beguines, the “order that was no order” that Mechthild of Magdeburg first joined when she left her comfortable home. The Beguines lived in cities for the most part, in households that were completely independent of church authorities. They supported themselves by spinning and weaving, and went about caring for the poor and the sick, eventually founding “Beguinages” that were themselves the size of small cities.

So yes, when I look about today and wonder where the Julians are, and the Mechthilds, I am guided by what I know about vernacular mysticism. I look deliberately for the improvisational and the local — the concrete and vivid and, yes, playful. Outsider-insiders. . .

The so-called “great man” theory of history was so foundational to so much for people in my generation that even if we think we’ve outgrown it (and a host of scholars are doing wonderful demolition work in this area), it continues to shape our thinking.

It wasn’t that long ago that I envisioned Julian and her sisters-in-spirit in a kind of heroic mold — Joan of Arc and then some — larger than life, scaling the heights of spiritual attainment — singular and sufficient unto themselves.

But the longer I listen to what they actually say about what happened to them, and the more closely I look at the lives of contemporary women who strike me as their great grand-god-daughters, I see something else. Feel it, rather...

What unites the mystics of every time, every place, every faith, and every gender is that they have come to know, unequivocally, that all of life is one: that we are all part of one another, and profoundly interdependent... that no one on earth is singular or sufficient unto herself.

Satya they call it in Sanskrit, the “is-ness” of everything and the one-ness of all that is.

But it isn’t static! I no longer think of that ultimate truth as just sitting there passively, waiting to be grasped. It’s out there, all around us, pressing in on us, almost desperately seeking any opening it can find. Call it Holy Spirit, or perhaps it is simply the next phase of human evolution — the one we must embrace if we are not to vanish altogether. What I had seen as the object of heroic striving I see now as the only subject that is, and that our part is in fact a tremendous letting go... an emptying out, a making room...

Mirabai Starr captures it exquisitely in her 2018 book, Wild Mercy. In her chapter on Shabbat, she writes of Shekinah:

“In the tradition of our Jewish ancestors, we imagine her as a beautiful woman who flies in through every window on wings of light, penetrating and saturating each of our hearts. Her name is Shekinah and she 'resouls' us.”

On wings of light, she flies in through every window...Perfect.

Thank you, Mirabai!

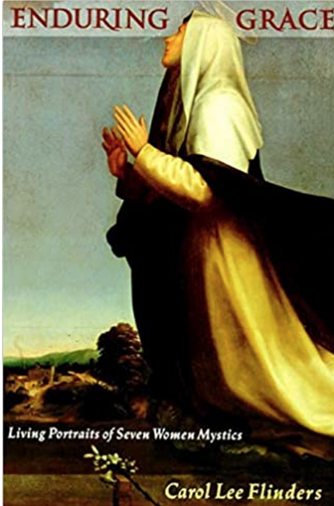

Born and raised in the Pacific Northwest, Carol Lee Flinders came to California for her undergraduate studies at Stanford and graduate studies at UCBerkeley. She co-authored the Laurel’s Kitchen cookbooks with other members of her community at the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation, and later — through the nineties and early "aughts" — wrote four books of her own, including Enduring Grace: Living Portraits of Seven Women Mystics and At the Root of This Longing: Reconciling a Spiritual Hunger and a Feminist Thirst.

Born and raised in the Pacific Northwest, Carol Lee Flinders came to California for her undergraduate studies at Stanford and graduate studies at UCBerkeley. She co-authored the Laurel’s Kitchen cookbooks with other members of her community at the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation, and later — through the nineties and early "aughts" — wrote four books of her own, including Enduring Grace: Living Portraits of Seven Women Mystics and At the Root of This Longing: Reconciling a Spiritual Hunger and a Feminist Thirst.

She has taught off and on, most recently at the Sophia Center for Culture and Spirituality at Holy Names University, where she co-taught the History of Mysticism with her husband Tim. The couple co-authored The Making of a Teacher as well as a son, Mesh Flinders.

Catalyst is produced by The Shift Network to feature inspiring stories and provide information to help shift consciousness and take practical action. To receive Catalyst twice a month, sign up here.

This article appears in: 2021 Catalyst, Issue 2: Mystics Summit